Uncovering Hidden Figures

History students are working to reveal hidden histories in Lane County, starting with stories of Jewish residents and Mexican, Mexican American migrants

Amid the Great Depression, the US government deported and repatriated hundreds of thousands of Mexicans and Mexican Americans, ostensibly to protect American workers.

But 142 migrant Mexican workers lived and worked on the outskirts of Lane County, helping to build and maintain railroads that spanned the region.

The stories of these workers, who lived and worked near the University of Oregon Eugene campus, went untold until students in a College of Arts and Sciences history class discovered them.

Photograph of Mexican railroad workers around the turn of the century in New Mexico. (courtesy El Paso Public Library from the collection Rescuing Texas History, 2009 by Aultman, Otis A., 1874-1943)

Photograph of Mexican railroad workers around the turn of the century in New Mexico. (courtesy El Paso Public Library from the collection Rescuing Texas History, 2009 by Aultman, Otis A., 1874-1943)

Led by Julie Weise, an associate professor in the Department of History who studies the history of migrations in the Americas, students in majors from history to business administration began researching and writing these local histories in June as part of a course series, which has attracted undergrad students in and outside of CAS. In Hidden Histories, they tell the stories of underrepresented communities in Lane County.

“A lot of people think that the only history of Lane County is white,” said Austin McKittrick, who graduated in June with a bachelor’s degree in cinema studies. “This gave us a sense that there were people of color in this county and they had an impact on the economic stability and the future of what it is today. And we shouldn’t forget them.”

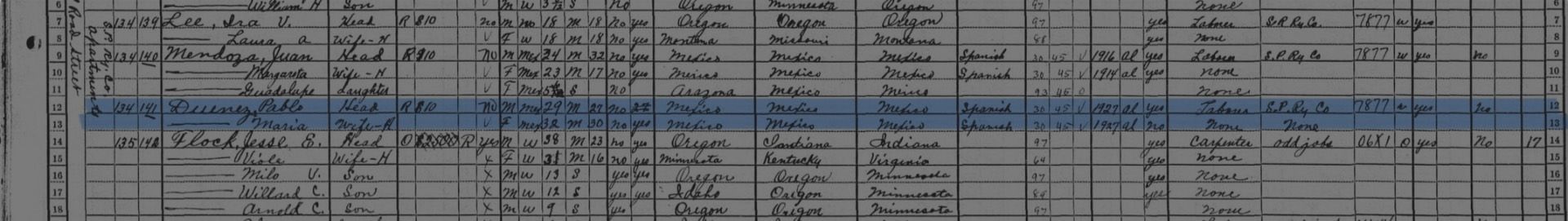

Students started with a 1930 US census database. From there, Weise and her students used documents via Ancestry.com and academic books about the period to develop the histories of 142 Mexican and Mexican American migrants in Lane County. Students published their findings as digital exhibits on a website and created high school lesson plans.

“It's just so great for the students because they actually are learning how historians do what we do,” Weise said. “I'm taking the exact method that I used to write about Mexican workers in Mississippi and New Orleans in this exact time period.”

Stranger in a strange land

While on a run in Eugene a few years ago, Weise realized that after living in Los Angeles, Mexico City and New Haven, she found the Pacific Northwest to be the first place where she felt alienated as a Jewish person.

“I’m a history professor. Maybe I can do something about this,” recalled Weise. “If I'm feeling this way, I'm guessing that other people who are not white and Christian may feel alienated, too.”

Weise worked with lecturer Rabbi Meir Goldstein of the Judaic Studies Program to secure funding from the UO Williams Fund to create Hidden Histories.

The series began in spring 2023, when Goldstein’s students analyzed oral histories of Lane County Jewish residents that had been created by the Lane County Jewish Federation and reside at the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education in Portland. The spring 2024 course focused on Mexican migrants in Lane County during the 1930s.

Weise plans to teach the course regularly, enabling students to create previously undocumented histories of people and cultures in Lane County. Franny Gaede, director of open research for UO Libraries, assists by building a website for the digital exhibits and helping students learn WordPress.

“We can do more Jewish history, queer history, Indigenous history, Black history,” Weise said. “The course will be there for any professor who wants to engage students in original research with some sort of public-facing product on Lane County's hidden histories.”

Railroad workers, circa 1930 (courtesy Oregon Encyclopedia)

Railroad workers, circa 1930 (courtesy Oregon Encyclopedia)

Increasing visibility of hidden histories

Weise is no stranger to telling the stories of Mexican communities neglected by mainstream histories. In fact, she recognized similarities in how history is told in the Pacific Northwest as it is in the South.

Her 2015 book, Corazon de Dixie: Mexicanos in the US South since 1910, covers Mexican and Mexican American communities that lived in areas such as the Mississippi Delta, where their histories weren’t taught in classrooms.

She later started the NuestroSouth.org public history project, a podcast that helps Latinx youth understand the Southern region of the US. For this, she collaborated with Latino youth who, she said, “talked pointedly about what it’s like to be raised where you don’t have a history, you’re learning about the civil rights movement and it’s like, ‘Which drinking fountain would we have drunk from?’”

Weise worked with Latino undergraduate students at Duke University and University of North Carolina to create social media content that interpreted the area’s Mexican migration histories, connecting the students to the area.

“They would always say how much it meant to them to know there were Latino people in the place [long ago], that their families didn’t just appear out of nowhere,” Weise said.

The US-Mexico border in the 1930s (courtesy University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries)

The US-Mexico border in the 1930s (courtesy University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries)

Undergraduates learn the art and science of history

Inside the Knight Library’s Dream Lab, a place reserved for digital learning, students sat in groups, wrapping up their histories and discussing their projects. It’s June, and for the past 10 weeks, students enrolled in CAS majors—as well as those outside of the college—have been introduced to the academic rigor and thought processes that historians rely upon when creating histories.

“I’m used to scientific research, but this was completely different, even though it’s still hands on,” said Justine Arias, a third-year environmental studies major. “It helped me learn the history better than sitting down and reading.”

Starting with names from a handwritten 1930 US census sheet, students searched databases and records and read through scholarly books to contextualize the lives of migrants in the US and Lane County.

“When you would look someone up, there’d be more than 100 results, and you’d have no idea if it were the same person,” McKittrick said. But family information like a spouse’s name or physical features—like a scar—could help narrow down searches.

Students found a history of people who built railroads, including the Southern Pacific Railroad, which was likely used for passengers upon for a growing timber industry in Lane County. Students wrote about railroad workers living in camps in Florence, Junction City, and Oakridge.

While digging into historical documents, third-year history major Juan Ochoa discovered a man named Antonio who owned a car. This was unusual for migrant workers in the 1930s, who often relied on crew leaders for transportation to the worksite.

Ochoa found that the worker was married to a woman a decade older in age. She’d had a husband and likely inherited money that allowed the worker to own a car.

This would have given him a financial advantage, Weise said, given that the crew leader was also the person workers bargained with for wages. Someone with a car could negotiate higher pay or leave a worksite he didn’t like.

Of the 142 Mexicans and Mexican Americans in Lane County, about 10 lived in Eugene’s city limits, including a man named Albert, a door-to-door kitchen appliance salesman, according to Sanchez. Ten years later, he and his family moved to Portland.

While sifting through documents and scouring through secondary literature, Weise provided the foundation and mentorship to help students work as historians, Sanchez said.

"Dr. Weise was helpful in showing us how to connect those dots and use things we learned from secondary literature to inform our opinions and our conclusions," Sanchez said. "It grounded our ability to think as historians do, especially in building these narratives and forming stories."

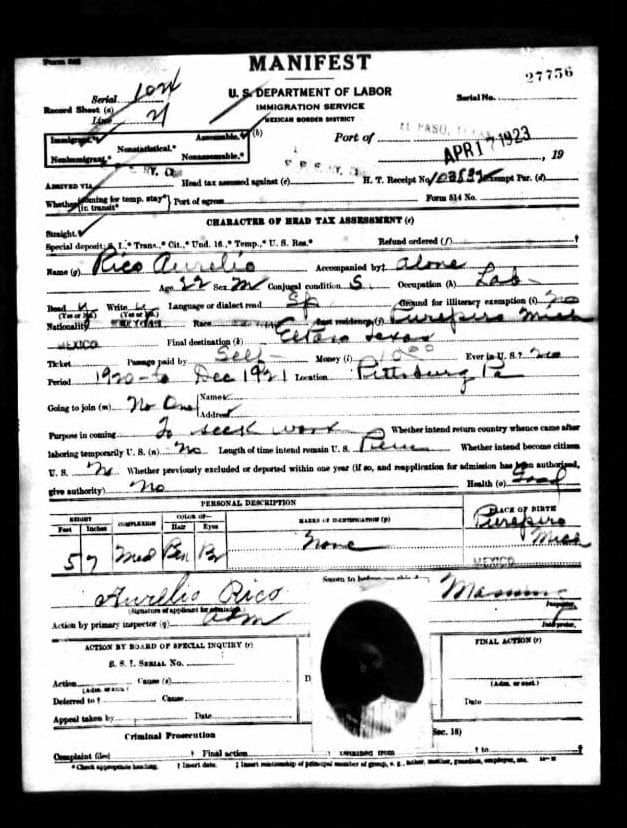

Border crossing record for a Mexican immigrant included a photo of him at the time of crossing. (photo courtesy The National Archives and Records Administration, available from Ancestry Library)

Border crossing record for a Mexican immigrant included a photo of him at the time of crossing. (photo courtesy The National Archives and Records Administration, available from Ancestry Library)

Junction City Front Street Railroad in 1936 (photo courtesy University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries)

Junction City Front Street Railroad in 1936 (photo courtesy University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries)

Teaching the Next Generation

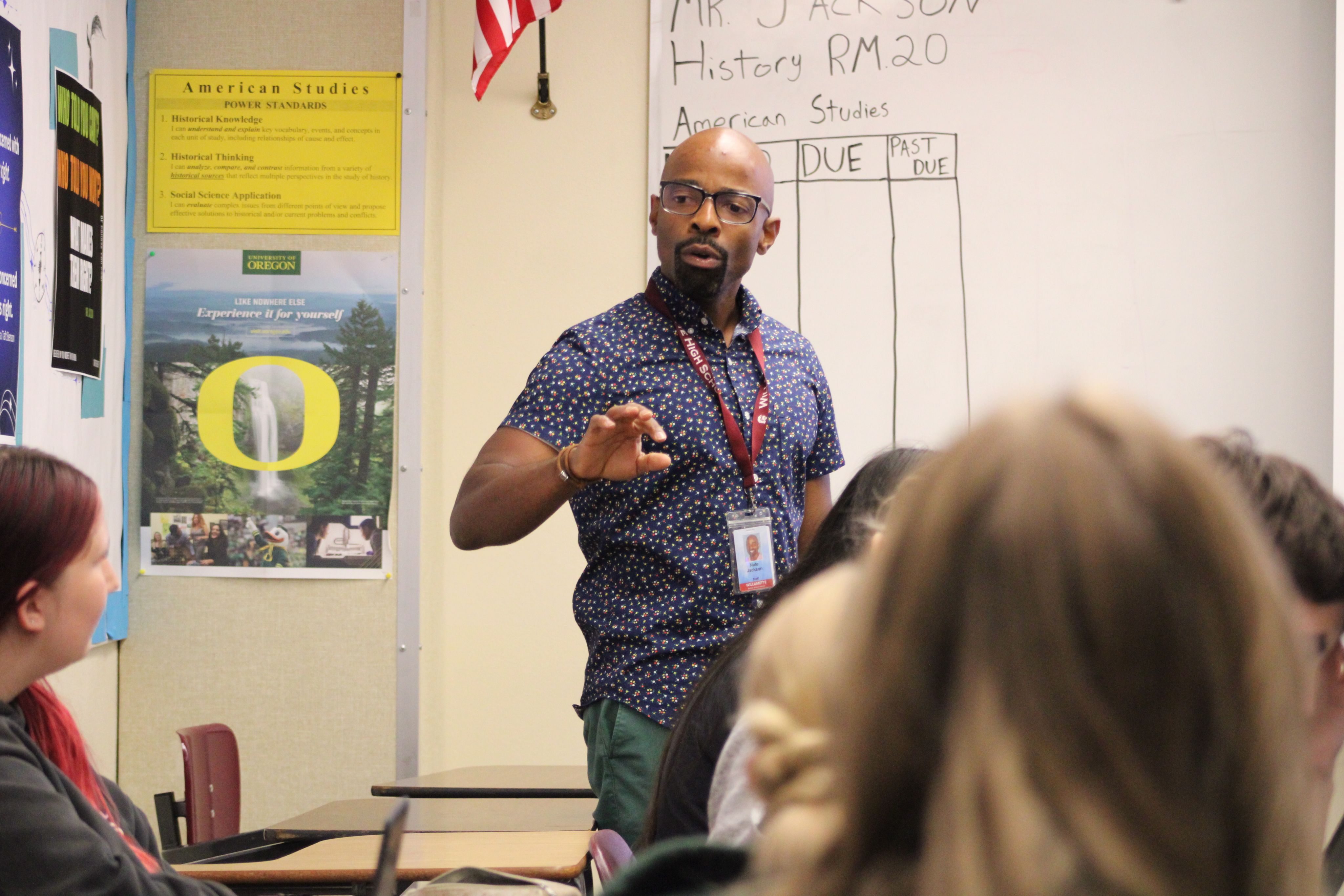

Alumnus Nate Jackson, who teaches American history, world studies and Black studies at Willamette High School, is looking into how to include the student-created Hidden Histories lesson plans in his classroom this school year. Weise is also reaching out to other high schools to share the students’ resources.

“When Julie said she wanted to introduce Latino history, I was thrilled to be a part of that,” said Jackson, (journalism, ’05). “As a history teacher, I look for ways to incorporate voices that are not heard as often in history.”

One approach he takes is contextualizing the Great Depression.

“If white people were at 25 percent unemployment, what was it like for Latinos?” Jackson asked. “And then we find out that Latinos were deported.”

Jackson is especially interested in Sanchez’s research on the car-owning Albert family’s economic mobility. It illustrates the push and pull factors of migration, Jackson said—specifically, what brings someone to an area and what pushes them out.

Sanchez, who plans to pursue a master’s in education after graduation in 2027, said he enjoyed turning his research into lesson plans.

“I’ve done lesson plans in the past, but nothing on research I’ve done,” Sanchez said. “There’s so much you want to get across, and you have to reduce what you want students to learn based on time.”

Jackson hopes other universities and colleges will follow the UO’s lead in collaborating with K-12 schools.

“I love what Julie is doing, and I love her heart, and I hope that what Julie's doing will inspire more educators to look for resources to help unearth the voices that are not taught in our classes,” Jackson said. “I'm glad that Julie is being aggressive about getting those voices heard, and I hope others do the same."